In all of my previous “Who’s Your Daddy” posts, I examined the parentage of one individual grape. Today’s “Who’s Your Daddy” is a bit different in that I’ll be discussing the parentage of, well, all grapes (specifically, all those that are in the USDA grape germplasm collection).

Research has found that grape domestication happened in the Near East about 6,000 to 8,000 years old, originating in South Caucasus between the Caspian and Black Seas. There are thought to be over 10,000 varieties of grapes throughout the world today, which appear to have a relatively high level of genetic

![Photo by John Reinhard Weguelin [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.academicwino.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/pressing_grapes_1880_The-Academic_Wino-201x300.jpg)

Photo by John Reinhard Weguelin [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

chance of widespread crop loss should a new pathogen rips through the nonresistant population. Maintaining different lines of genetic diversity is crucial to avoiding total crop loss..

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has a “grape germplasm collection”, which is a collection of grape seeds of ample genetic diversity to help replace plants when they are exposed to new pathogens of which they have no resistance. Out of the thousands of varieties of grapes, the USDA maintains a library of 950 vinifera germplasms. Of these, 58% of are clones of at least 1 other germplasm, with 583 of them unique cultivars.

One fascinating thing about grape breeding is that since it’s a vegetatively propagated outcrossing perennial species, ancient cultivars spanning back thousands of years can still coexist with modern cultivars. Despite the potential for great genetic diversity, relatedness between cultivars remains relatively

![Population bottleneck: Imagine the red line is when a small number of Vinifera grapes were moved from France to North America. What happens is that the genetic diversity drops significantly due to the drastically reduced population size in the new region. Then, eventually propagation occurs in the new region, though may not recover to the same level of genetic diversity as the original population due to the lower population numbers to start. Photo by TedE [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/), GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], from Wikimedia Commons](http://www.academicwino.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Population_bottleneck_The_Academic_Wino-300x254.png)

Population bottleneck: Imagine the red line is when a small number of Vinifera grapes were moved from France to North America. What happens is that the genetic diversity drops significantly due to the drastically reduced population size in the new region. Then, eventually propagation occurs in the new region, though may not recover to the same level of genetic diversity as the original population due to the lower population numbers to start.

Photo by TedE [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/), GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], from Wikimedia Commons

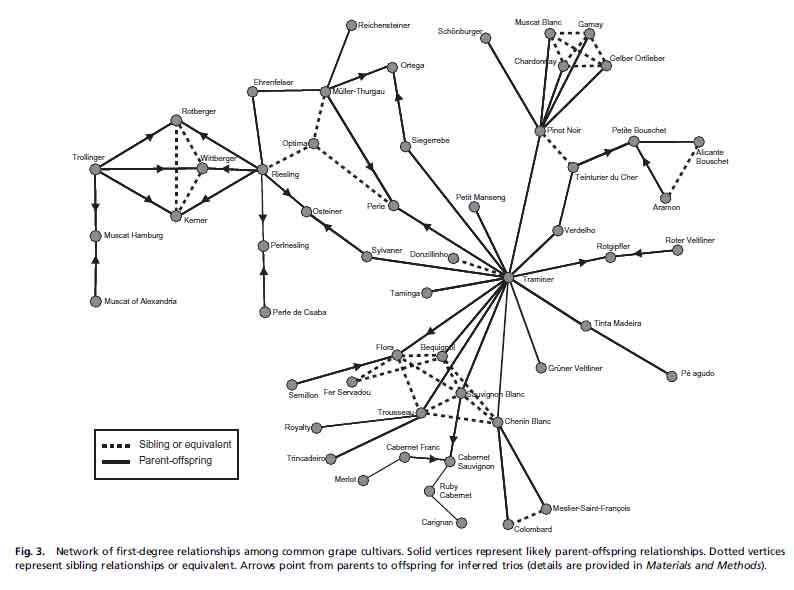

From these direct relationships, 47.6% were calculated to be parent-offspring relationships, while the other 52.4% were calculated to be siblings or some equivalent. Analysis also confirmed a probable Near-East origin of the domesticated grape, with all vinifera cultivars being more closely related to Eastern sylvestris cultivars than Western sylvestris cultivars (sylvestris = wild grapes). Also, genetic diversity in the Western vinifera cultivars was found to be less genetically diverse than Eastern vinifera cultivars, suggesting some sort of population bottleneck, which can occur in extreme climate changes, human activities, or geographical isolation. After this bottleneck, it seems to be that propagation of different cultivars remained relatively low in the West, thus keeping the numbers of unique cultivars lower than they were in the East where their propagation practices were more complex.

The analysis of the USDA collection indicates that the interrelatedness between different vinifera grape cultivars is extremely close, and that overall the percentage of possible genetic variants in the population is very low. In order to adjust to a changing climate with unknown roadblocks ahead, it may be crucial to maintain greater genetic diversity of wine grapes so as to avoid possible total wipe-outs of entire cultivars.

Figure 3 from Myles et al (2011) showing the first-degree (direct) relationships among grape cultivars in the USDA collection. Solid lines represent parent-offspring relationships, while dotted lines represent sibling or equivalent relationships.

In a way, we’ve already been warned about the consequences of such a disaster. Just look at the 19th century Phylloxera crisis. Vineyards all over the globe had been nearly eliminated by the invasive pest known as Phylloxera. Since they all were so tightly interrelated, not a single cultivar had the genetic makeup necessary to provide resistance against the pest. In fact, only a small number of native grapevines from North America were resistant against the pest. Had there been greater genetic diversity in the wine grapes, some cultivars may have survived and could have kept the industry going without having to search the globe for alternatives. If we want to avoid another crisis that could potentially wipe out the entire wine industry, we need to plan ahead and start increasing genetic diversity of the wine grape.

With a changing climate, some grape cultivars will probably not survive. Developing more genetically diverse cultivars from the current stock may allow the wine industry to have a better chance at success regardless of what Mother Nature throws in the way. We are already seeing some progress in this area, particularly with the Grape Genetics Research Unit in the Finger Lakes region of New York in the USA, though much more needs to be done. I’m encouraged by the work that has been done so far, and only hope this type of work continues and becomes more mainstream in wine industries around the globe.

1 comment for “Who’s Your Daddy: Family Tree and Future of the Species Edition”