The following is a guest post by Emily Kate from the History of Wine Channel on YouTube. You may also visit her website, The Wine Historian. Please see the end of this post for her full bio.

Despite its benefits, consumers and professionals alike seem to have a hard time accepting the bag-in-box wine cask in lieu of the classic wine bottle. But just how classic is the bottle? Wine has been kept in all sorts of containers throughout history varying in size, shape and material. Each form has had its own advantages, caveats, eccentricities and drawbacks. Let’s take a look back through the historical morphology of wine’s most widely utilized vessels.

The Bible indicates the prevalence of wineskins and highlights their ease of transport. In biblical sources, wine was brought home from the fermentation vat in a wineskin and travelers, including David and the Gibeonites, favored the wineskin for its lightness. But more permanent storage for a higher volume of wine was also necessary and came in the form of pottery. In biblical as well as antique sources, large jars were utilized both above ground for high volume transport as well as partially buried for preservation. For millennia, these large earthenware jars were used to ferment, store and transport wine.

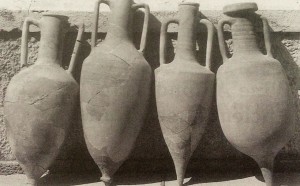

Figure 1: Roman Wine Amphorae. Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade by Tim Unwin

Figure 2: Amphorae from the debris of the destruction of Athens by the Romans in 86 BC. Wine Amphoras in the Ancient Greek Trade by Carolyn G. Koehler

Whereas the Romans called their large earthenware jars, dolium, the Greeks named them pithoi. With the exception of Campania in Italy, the Greeks were more masterful at the art of pottery than the Romans. In order to make their containers air and watertight, the Romans used heated resin known as pitch to line the dolia and plaster to patch them where needed. The advantage of airtight containers was acknowledged by first century AD Roman agronomist Columella who warned his readers against buying ollas bibulas aut male coctas, or jars which are porous or badly baked, and advised them to apply an inner lining and outer coating to the jars to create a tighter seal for the wine. In the second century BC, Roman statesman Cato the Elder spoke of the dolia as a fermenting vat, and explained that after thirty days of “boisterous fermentation,” when the marc, formed of pips, skins, and stalks, has been fully cleared, the wine should be racked off into amphorae.

Amphorae are slightly smaller than dolium, which contain 2-3 thousand liters, and typically have a pointed bottom. Much research has gone into understanding the way amphorae were stored and utilized. The possibility exists that they were stored upright and dug into the ground using their pointed bottoms, much like we might plant a beach umbrella in the sand. Archeologists have discovered ring stands that prop the jars upright, but these were most likely used while extracting wine. It is also plausible that amphorae were laid on their sides, with the liquid keeping the stopper moist and the seal airtight. There are rope mark embellishments found in a U-shape on the sides of some amphorae which could indicate placement of actual rope used to provide stability and support once the vessel was on its side.

Interested in learning more about the history of art on wine artifacts? Check out this video:

The remnants of liquid found inside many vessels also support the hypothesis of horizontal storage, as reddish stains stretch the length of the interior on one side, as though sediment and liquid had settled. There is also a small hole along the reddish stain, just above the bottom of the amphora, drilled after the clay was fired which is thought to have been used to decant the wine, draining it off the sediment. When not being drained out through a hole, the wine was commonly ladled out of jars using a cyathus, a cup with a long handle. When closed, these amphorae were so tightly sealed that they were able to preserve wine and facilitate longevity which accounts for the vintage wines attested to in antique sources. Odysseus’ Homeric cellar, reputed to have amphorae of fine wines lined up by year, is a prime example of the cultivation of vintage wine collections in antiquity.

Figure 3: Import wine casks being towed inland. Ostia. A History of Wine: Great Vintage Wines from the Homeric Age to the Present Day by H. Warner Allen

Around the second century AD, amidst the popularity of terracotta jars, the use of wood slowly crept into the wine industry. Cato spoke of using planks of oak wood to strengthen earthenware fermenting vats but not using wood by itself. When first century AD Roman naturalist Pliny first referenced the use of wood, he spoke of the alpine practice of racking off wine into wooden casks girded with round hoops which he called, lignea vasa. In addition, the rising popularity of wine in Gaul facilitated the widespread use of the cask, as the Gauls could not master the art of pottery at the same level as the Italians and Romans. The Gauls excelled in making wine called picatum, which they put into their wooden casks and traded with Italy and Greece. Still, amphorae remained the container of choice in Italy and Greece for another 150 years. And thus, as confirmed by both Trajan’s Column as well as a mosaic at Ostia, the trading of wine in each civilization’s respective containers continued simultaneously.

Figure 4: Roman Wine Boat with Cargo of Amphorae, second or third century AD. Mosaic from Tebessa in Algeria. A History of Wine: Great Vintage Wines from the Homeric Age to the Present Day by H. Warner Allen

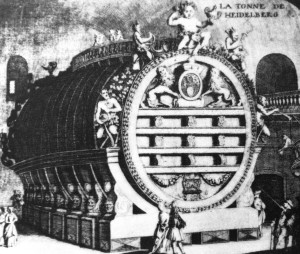

Eventually, the terracotta jar fell out of favor and the barrel took its place. Barrels of all sizes were created including the tun, which is the measure of wine used in most import and export documents of the Middle Ages. The wood, however, did not provide an airtight seal and wine quickly turned while stored inside wooden casks. Without an understanding of why the wine was spoiling, winemakers weren’t properly bunging or topping off their casks and people simply began to consume increasingly younger wines. This practice ushered in the absence of vintage wines in the medieval period.

Figure 5: The Great Tun of Heidelberg. A History of Wine: Great Vintage Wines from the Homeric Age to the Present Day by H. Warner Allen

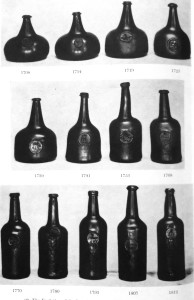

After centuries of dominance by the wooden cask and the resulting need to drink wines quickly before they turned to vinegar, vintners began seeking an alternate container. In the eighteenth century, physician and politician Sir Edward Barry observed the Port shippers’ attempts to age wine in bottle and associated the practice with aging wine in the ancient amphorae. At that point, it was not known that the invasion of hostile microbes was harming the wine; rather, the cause was thought to be the changes in atmosphere around the container. Although the bottle had already existed, it was used primarily as a midpoint to get the wine from the barrel to the cup. Corks were not well-fitted as they were simply meant to keep bugs and dust out, not to create an airtight seal. Bottles had previously been seen as an unreliable measure of wine as each was individually blown by a glass blower and, in turn, held inconsistent volumes of liquid. Modeled after the Port bottles of the time, the original wine bottles were short and squat with protruding necks. This shape made them impossible to lie on their sides, and forced them to be stored upright.

Interested in learning even more about history of wine artifacts? Watch this video:

Figure 6: The Evolution of the Port Bottle: dated bottles from the collection of Messrs. A History of Wine: Great Vintage Wines from the Homeric Age to the Present Day by H. Warner Allen

It was Henry Purefoy who discovered that when the cork was not submerged in liquid, it shrank due to dryness and resulted in spoiled wine. It was only when the bottle was laid on its side and the cork submerged that it could accomplish long-term preservation similar to the amphora. This revelation led to the change in bottle shape of the 1740s from a short and stout bottle to an elongated bottle like we have today. A few decades later, the shape became more cylindrical to facilitate easier disposal. This evolution enabled the return of vintage wines, as maturation and longevity were possible once again.

Given the historical precedent for change in wine containers, the bottle shouldn’t be heralded as a classic as it is a relatively modern concept. Although seen as an inelegant solution, the bag-in-box cask should not be dismissed. Since Louis Pasteur’s famous discovery concerning oxygen’s harmful effects on wine, the industry should be compelled to embrace the progression towards a new container that provides non-cellar worthy wine with better protection from oxygenation. The industry has been more accepting of accessories that alter the effects of the problem rather than the container that aims to eliminate it. If the bottle was a return to the airtight ancient amphora, the bag-in-box is an homage to the malleable biblical wineskin. Considering that it took the Greeks and the Romans nearly two centuries to convert to the Gallic barrel, perhaps the industry will come around to Australia’s cask by 2100.

Emily Kate is a History student at Columbia University with a specialization in the history of wine. In addition to her studies at Columbia, she has attended the Wine and Spirit Education Trust: International Wine Center where she has earned her Intermediate and Advanced certification with honors. Emily has interned at wineries in the United States and Australia, and will learn about the retail aspect of the wine industry this summer in New York City. She has combined her passion for wine,education and technology to create her YouTube channel, History of Wine and the Vine.

Sources Used and Suggestions for Further Reading

A History of Wine: Great Vintage Wines from the Homeric Age to the Present Day by H. Warner Allen

Wine, Wealth and the State in Late Antique Egypt: The House of Apion at Oxyrhynchus by T.M. Hickey

The Origins and Ancient History of Wine Edited By Patrick E. McGovern, Stuart J. Fleming and Solomon H. Katz

The Archaeological Evidence for Winemaking, Distribution and Consumption at Proto-Historic Godin Tepe, Iran by Virginia R. Badler

An Enologist’s Commentary on Ancient Wines by Vernon L. Singleton

Canaanite Jars and the Late Bronze Age Aegeo-Levantine Wine Trade by Albert Leonard Jr

Wine Amphoras in Ancient Greek Trade by Carolyn G. Koehler

Wine and the Vine: An Historical Geography of Viticulture and the Wine Trade by Tim Unwin

The Fruit of the Vine: Viticulture in Ancient Israel by Carey Ellen Walsh

Studies in the Medieval Wine Trade by Margery Kirkbride James

History of the Wine Trade in England Vol. I & II by A. L. Simon

Mead and Wine: A History of the Bronze Age in Greece by Jean Zafiropulo

In Vino Veritas Edited by Oswyn Murray and Manuela Tecusan

Wines of the World by A. L. Simon

2 comments for “The History of Wine Containers: Featuring Guest Writer Emily Kate”