Disclaimer: While this post has a sponsor, all facts and opinions expressed are those of the research article I am presenting as well as my own, none of which have been influenced in any way, shape, or form by the sponsor. Enjoy!

Earlier this summer, it was widely reported that Resveratrol supplements, could negate the cardiovascular benefits of exercise in adult men, with the source coming from research by University of Copenhagen researchers in The Journal of Physiology on July 22nd. Science Daily, CBS News, Iron Magazine, and many other news and resource outlets reported these findings, and the news that resveratrol supplements may cause negative cardiovascular effects during exercise spread like wildfire. (To read these various articles, simply click on the links associated with each resource).

Just reading the quick summary about this research is certainly alarming, but was it a little TOO alarming? In

other words, could the results of the study have been blown out of proportion or misinterpreted?One of the great things about scientific research is the fact that the questions and research does not stop once an article has been published. Even after the work has been through peer review and has hit the press, other researchers have a chance to critique the work further, which allows them to continue to advance the line of research, or note serious flaws that may have been missed the first time around. It is important with any research to not only focus on the conclusions given by the authors, but to also have a general understanding of the scientific method and the methods that were taken in order to lead to the results and conclusions that have been presented. This is important not only for health-related studies, but for all research studies in every field.

Several experts have stepped forward to vehemently disagree with the conclusions of the Copenhagen study, including Dr. David Blyweiss from advancednaturalmedicine.com, as well as two researchers from High Point University and Wilmore Labs, LLC, respectively, with the latter two having their rebuttals published in The Journal of Physiology just last week.

The primary conclusion from the Copenhagen study was that “exercise training effectively improves several cardiovascular health parameters in aged men, [but] resveratrol supplementation blunts most of these effects”. James M. Smoliga from High Point University and Otis L. Blanchard from Wilmore Labs, LLC, in their letter published in The Journal of Physiology last week, though impressed with the overall nature of the study and the methods by which the study was performed, took great disagreement with the overall conclusions made by the Copenhagen researchers based upon the results obtained.

Smoliga and Blanchard take issue with several points:

1. The statement that resveratrol supplements blunt most of the effects of exercise and produces mainly negative effects.

- Smoliga and Blanchard disagreed with this statement based on the results that showed that only 2 of the 45 variables studied actually showed slight negative effects in the resveratrol group compared with the control group.

- 12 out of the 45 variables actually showed improvement in the resveratrol group compared with the control group.

- Finally, there were no post-training differences between groups for most of the variables, indicating that interpretation of differences during exercise might be more complicated that what was reported in the Copenhagen study.

i. Example: In the control group, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol), was significantly decreased (0.3 +/- 0.2 mmol/L). In the resveratrol group, there was also a decrease in these levels, though it was not statistically significant (0.2 +/- 0.2 mmol/L). Smoliga and Blanchard disagreed with the Copenhagen study that resveratrol supplements“abolished” the positive effect of exercise on the decrease of “bad” cholesterol, as the difference was not great enough to justify these strong statements.

2. The statement that resveratrol supplements “did not affect the retardation of atherosclerosis”.

- Smoliga and Blanchard took offense with this statement, based on the knowledge that not one subject in the study had any cardiovascular disease whatsoever. Their rebuttal states that “it [is] unreasonable to expect for resveratrol to reverse a condition that did not exist.”

- I tend to agree with Smoliga and Blanchard on this point—it’s difficult to make a statement on the protection against cardiovascular disease when, in fact, none of the subjects ever had any of these related problems.

3. The statement that “resveratrol supplementation caused a shift in vasoactive systems favoring vasoconstriction”.

- Smoliga and Blanchard claimed that the results from the tests related to this statement was rather mixed, and those clinical tests performed did not support such a statement.

4. The statement that “resveratrol supplementation combined with exercise training induced a 45% lower increase in maximum oxygen uptake than training with placebo [i.e. control group]”.

- Smoliga and Blanchard disagreed with the use of maximum oxygen uptake as the appropriate variable for this analysis, and that the absolute magnitude of the difference between maximum oxygen uptake would be more useful here.

i. In fact, when calculating the absolute magnitude of the difference between maximum oxygen uptake between resveratrol and control groups, the difference was very minor, and potentially not significant in any clinical setting.

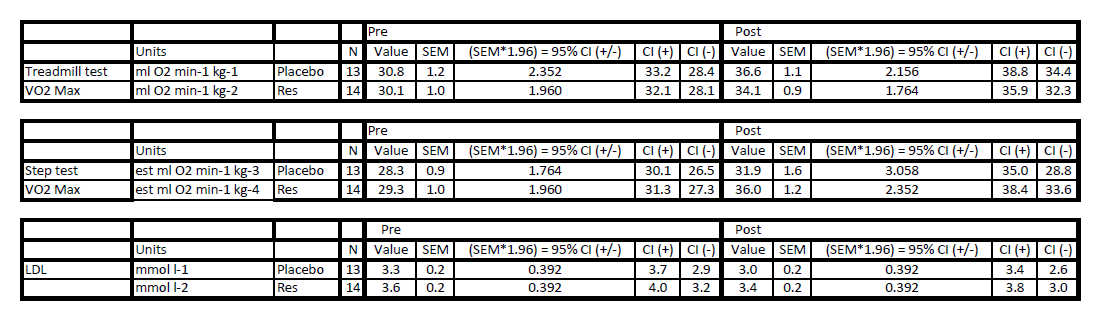

- For one exercise test in particular (the bench step test), the resveratrol group showed a significant 86% improvement in maximum oxygen uptake compared with controls, yet according to Smoliga and Blanchard, this fact was skipped over by the Copenhagen study. See figure below for the analysis of this supplemental data by Smoliga and Blanchard (click to enlarge):

Supplemental Data from Copenhagen study analyzed by Wilmore Labs, LLC and High Point University researchers

5. The statements attributing the differences between the “negative” results found in this human study with the “positive” results found in animals studies.

- Smoliga and Blanchard looked into these comparisons and argued that the Copenhagen study should not have made these general statements based simply on the fact that the dosages used in these studies were completely different from one another, and thus may not be directly comparable.

- Directly from Smoliga and Blanchard: “Given many unknowns regarding the dosage for resveratrol to influence specific outcome measures in humans (especially in individuals without overt cardio-metabolic dysfunction), it is important to avoid generalized conclusions referring to resveratrol supplements as a whole, but rather report conclusions specific to the dosage used.”

If these points regarding potential faults in the Copenhagen study are valid, what does this mean for the progress of resveratrol supplement research?

“When bad science is published and sensationalized, being positive or negative for Resveratrol, it hurts progress in the field, either by setting unrealistically high expectations or unjustifiably tarnishing the reputation of the field. It has really hurt us. We (Wilmore labs collaborating with High Point University) have been working on a new dosage form of Resveratrol. From our proof-of-concept data, it safely provides levels of Resveratrol 20 times higher than used in the Gliemann study [i.e. the Copenhagen study], in humans, and this may allow us to see somebenefits observed in previous animal research. The dosage may also solve the problem with GI irritation while limiting cost. It would about a semi-tanker of red wine to equal the same dosage of Resveratrol our test delivered. Because of the mass attention the Gliemann study received, with its errors, we are having difficulty securing investment for future development, and our work may never reach its true potential. Scientists, and the media, must take greater accountability for the integrity of their work” -Joint

The Academic Wino’s Concluding Thoughts

“One study does not a scientific conclusion make.” ~Lewis Perdue

I feel as though it is important to keep an open mind when reading anything, including scientific research, and not to make sweeping conclusions based upon the reported results of one individual study. The media and others should take heed of this as well, and thoroughly analyze and research something before sensationalizing something that may or may not be correct (case in point: the recent claim that we’re going to suffer from a worldwide wine shortage, which turn out to be based on faulty analysis). It is the combination of many studies that allows one to claim stronger conclusions on any given subject.

I believe Smoliga and Blanchard make some valid points in their letter of rebuttal to the Copenhagen study, though I also agree with them that the study itself was very interesting and could provide some valuable information. I plan to follow up with the researchers involved with the Copenhagen study to get their response to these critiques by Smoliga and Blanchard.

My biggest beef with the sweeping conclusions that were made on this study was that they were based off results from a tiny sample size. There were only 27 subjects participating in this study, with 14 of them randomized into the exercise + resveratrol group, and the other 13 randomized into the control group (exercise and no resveratrol). This sample size is very small, and thus makes it extremely difficult to generalize the results to an entire population. Even if there were no other problems in the interpretation of results, the fact that the sample size was so small is concerning for blanket generalizations.

Another thing that got me thinking after reading this rebuttal was “why are we always so focused on resveratrol, anyway?”. Sure, resveratrol is the most commonly studied polyphenol in wine, however, many studies have found that there are many comparable compounds with similar, if not better, antioxidant, anti-radical, and otherwise beneficial characteristics for human health (see an example in one of my posts here). In my opinion, based on many of the studies I’ve reported and/or read over the years, is that resveratrol does not act alone to provide many of the health benefits that have been shown for red wine. It is likely the work of

![Photo By Ragesoss (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.academicwino.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/supplement_tablets_the_academic_wino-300x239.jpg)

Photo By Ragesoss (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

I think this is one of the main problems with this sort of red wine supplement research out there, in that too many are focused solely on resveratrol. What about a sort of “wine multi-vitamin”? How about we mix in some resveratrol, catechin, and anthocyanins? While these studies focusing on resveratrol are useful in some ways, I think expanding the repertoire of natural ingredients found in red wine to include a more balanced (and thus more representative) “red wine pill”, may possibly be the supplement that some are looking for.

Of course, if you’re not into supplements, just eat right, exercise, and drink wine in moderation, and hopefully you’ll be fine!

What do you all think of this topic? Did the Copenhagen study jump to conclusions that were unreachable? Are the points brought up in the rebuttal valid? Are the points brought up moot? Do you have further questions or is there some research you’d like to see done that has yet to be addressed? Please feel free to leave any/all comments! Cheers!

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: “Otis Blanchard is the owner of Wilmore Labs LLC, which has a commercial interest in the development of novel resveratrol formulations”.

Further Recommended Reading/Sources:

- Gliemann, L., Schmidt, J.F., Olesen, J., Biensø, R.S., Peronard, S.L., Grandjean, S.U., Mortensen, S.P., Nyberg, M., Bangsbo, J., Pilegaard, H., and Hellsten, Y. 2013. Resveratrol blunts the positive effects of exercise training on cardiovascular health in aged men. The Journal of Physiology. Available online: doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2013.258061

- Smoliga, J.M., and Blanchard, O.L. 2013. (Letters) Recent data do not provide evidence that resveratrol causes ‘mainly negative’ or ‘adverse’ effects on exercise training in humans. The Journal of Physiology 591.20; 5251-5252.

- Researchers Challenge Conclusion that Resveratrol Lessens the Benefit of Exercise (PRWeb)

- Too Many Antioxidants? Resveratrol Blocks Many Cardiovascular Benefits of Exercise (Science Daily)

![Photo By National Institutes of Health [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.academicwino.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Elderly_exercise_the_academic_wino.jpg)