The following is a guest post (as promised) by Arthur George. He is a retired lawyer who now resides in Santa Barbara County, California wine country, who now spends his time as a “winemaker, author, mythologist, cultural historian, and blogger”. Most recently, he has been lecturing and writing about the subject of the mythology of wine, which is a subject not often discussed in the wine business, but one which is completely fascinating and worthy of further exploration.

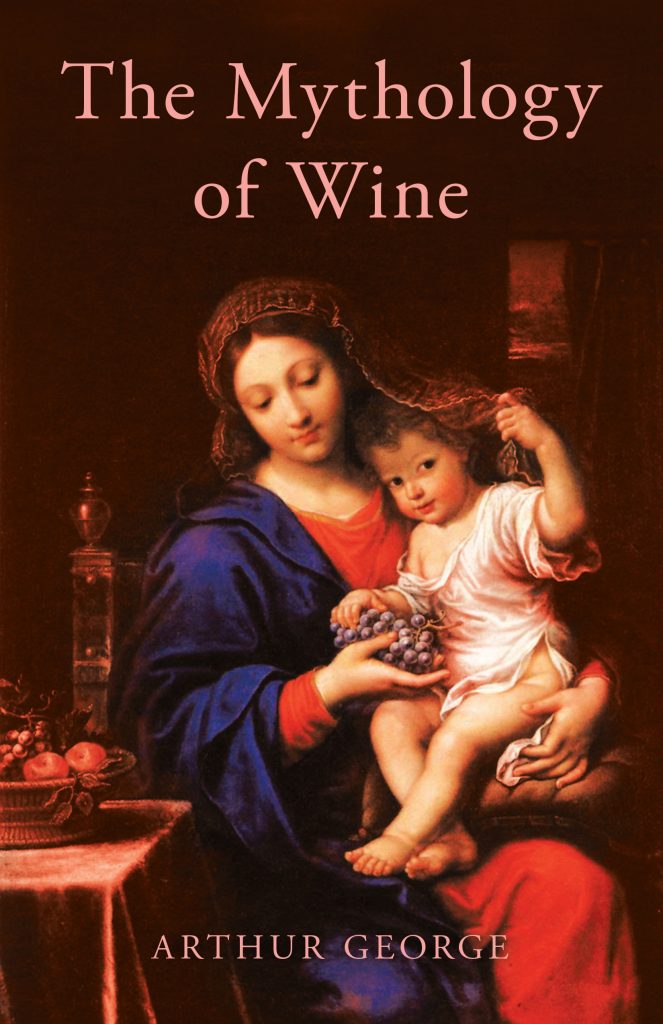

His new book, The Mythology of Wine, which I reviewed last week, is now available for purchase. Feel free to click the link to read the review or click here to go directly to Amazon (disclosure: if you buy from the Amazon link, I might get a few pennies).

All images included in this post were given by Arthur George with permission to publish.

Without further ado, here is the guest post by Arthur George:

The popular image of Dionysus is often that of his Roman incarnation, Bacchus, pictured as overweight, red-faced, and slouching back in a drunken stupor. But Bacchus has no mythology behind him other than what he drew from the truly interesting Greek Dionysus, whose roots are ancient. This post describes how and why Dionysus became Greece’s wine god. But first we must understand why wine came to be associated with the divine and deities in the first place.

How Wine Myths Arose

The ancients didn’t understand how fermentation worked, or what yeast and alcohol were. They thought that the inebriating effect of wine was a supernatural event: Wine had divine qualities, allowing the drinker to connect with the divine and to deities. Deities were thought to be responsible for wine, so wine myths and rituals involving these deities developed. The gods were thought to drink wine, so people made wine offerings to them.

Since wine comes from grapevines, the divine qualities of wine were attributed to the vine and grapes as well; they too were associated with deities. Their divinity was evidenced by the vines going into dormancy in the winter (a kind of death) and renewing each spring to produce divine grapes. This was the divine life force in action, the most important aspect of divinity for people in the ancient world. While all plants and animals were thought to have the divine life force in them, grapevines were considered supercharged, the force’s highest expression on earth. This force was not just that of ordinary life which comes and dies (bios in Greek), but eternal, indestructible life (zoe).

People could experience the divine when they drank wine. The wine god was in the wine and was the wine. The wine drinker connected with and experienced the deity first-hand. This placed Dionysus closer personally to the worshipper than with other, more distant gods, who seemed not to have cared much about humans. One had a relationship with Dionysus. And because Dionysus embodied zoe, eventually he was thought to confer immortality to his followers. (This is why wine was placed in tombs and other burials in the ancient world, to provide for the deceased in the afterlife and to help in being reborn.) These qualities tended to make Dionysus a personal savior, unlike with other deities.

Viticulture and winemaking involved working with the divine, and so were sacred activities. This meant that the resulting product, wine, represented the pinnacle of human civilization, at least in the field of agriculture. Symbolizing higher culture, it became the preferred beverage of civilized peoples, especially among royalty and aristocrats. The gods drank it too. Dionysus was the patron of winemaking and winemakers, and so too of higher culture. He inspired both the symposium where high ideas were discussed, and also the development of Greek theater.

The Birth and Resurrection of Dionysus

Zeus had an affair with a mortal woman, Semele, getting her pregnant with Dionysus. When Zeus’s wife Hera learned of this, she resolved to kill Semele and the fetus. She appeared before Semele disguised as her nurse and convinced her to ask Zeus to see him in his full glory. Zeus had promised never to refuse Semele’s requests, so when he appeared in his glory she was incinerated. The fetus was still intact, however, so Zeus sewed it into his thigh and brought it to term. When Hera learned of this, she sent Titans to kill the infant. They tore him to pieces, but Zeus incinerated them with his thunderbolt, and Persephone (who represented the rebirth of vegetation in the spring) reconstituted Dionysus from his heart. Thus Dionysus underwent a death and resurrection, enabling him to represent the continuity of life. He was raised by nurses, who became the god’s followers once he matured. He traveled far and wide, spreading his teachings — as far as India, as a result of which he was symbolized by tigers, panthers, and other large cats.

The Cult of Dionysus

Before the rise of viniculture, an early version of Dionysus was associated with honey and its fermented alcoholic beverage, mead, and with also beer; he was also associated with ivy, since it is an evergreen plant symbolizing the continuity of life. But with the arrival of viniculture Dionysus naturally assumed the role of wine god, and his associations with mead and beer faded. His cult object was a staff (thyrsus) twined with grapevines and/or ivy, often with a pine cone on top, representing the perpetuity of life.

Based on the tradition that Dionysus was brought up by nurses who became his followers and knew him best, the god’s worshippers originally consisted of groups of married women. They would gather at night in the hills or mountains outside the towns, without any men. They wore their hair down and dressed in long chitons, sometimes also wearing the dappled skins of fawns or large cats. They played music, danced, drank wine, handled snakes, and were said also to tear animals apart and eat the raw flesh (reenacting Dionysus’s own dismemberment). So they drank the god’s essence (blood of life) and ate his flesh, thus absorbing his divine essence. Through this ritual, the women worked themselves into a state of ecstasy or “madness,” hence their name: maenads (meaning “the raving ones”). This enabled them to experience Dionysus within themselves.

The Arrival of Viniculture and Dionysus in Greece

According to mythical traditions, Dionysus was not native to Greece but arrived there from across the sea, either from Crete, Canaan, or Lydia in Anatolia (Bacchus was the Lydian name for the god). Indeed, viniculture seems to have spread to Greece from these same locations. In myths and legends, initially ancient kings were given credit for discovering wine, for which they were admired as culture heroes, but later myths developed in which Dionysus was given credit for introducing them to wine. For example, Dionysus visited king Oineus in Aeotolia and fell in love with his wife, Althaea. Not daring to oppose a god, Oineus discreetly left town so that Dionysus could have his way. In thanks for Oineus’s hospitality, Dionysus gave him a vine, showed him how to cultivate it, and ordered that the vine be named oinos, which became the Greek word for wine.

A separate strand of myths gives varying accounts of how and where Dionysus arrived in Greece. Most of them recount how Dionysus initially encountered opposition from local communities, how Dionysus demonstrated his godly power and punished his opponents, and how his cult was then accepted. He typically demonstrated his godly power by making grapevines and wine appear.

One such myth involved the three daughters of Minyas, king of the Boeotian town of Orchomenos. The cult of Dionysus had recently arrived there, and most women went to the forest as maenads to venerate him. But Minyas’s daughters refused to go, preferring to stay at home and tend to their weaving, traditional women’s work. Angered by this disrespect, Dionysus appeared before them as a maiden, warning them not to neglect Dionysus’s rites, but they did not obey. In response, Dionysus appeared to them as a bull, then a lion, and finally as a leopard. He made ivy and grapevines grow over the daughters’ looms, and serpents to appear in their baskets of wool. Realizing their offense, they drew lots to decide which of them would sacrifice her child, whom they proceeded to tear to pieces. Then they dressed as maenads and went to the mountains to venerate the god. But it was too little, too late. After wandering the mountains for some time, they were turned into a bat, an owl, and a crow.

The most famous such myth is recounted in Euripides’s play The Bacchae, set in Thebes. Again, the appearance of Dionysus’s cult precedes his own appearance. Most Thebans oppose it, especially the king, Pentheus; they claim that Dionysus’s father was a mortal, not Zeus, meaning that he is not a god. Pentheus begins arresting supporters of his cult. Dionysus arrives as a handsome youth and is not recognized, but Pentheus arrests him, correctly sensing that he is a proponent of the new god. Dionysus escapes his chains using his powers. Pentheus now hears that a band of women has gone to the mountain to practice the god’s rites; one is Pentheus’s mother, Agave. At one point in the rites, a maenad strikes the ground with her thyrsus, “and the god at that spot put forth a fountain of wine.” Pentheus wants to arrest them but Dionysus, pretending to help, persuades him to go to where the women are, disguised as a maenad, and observe them. When he arrives, he climbs a tree to get a better view. The crazed women notice and attack him, thinking he is a mountain lion. They tear him to pieces. Agave personally carries his head back into town, and then realizes in horror what she has done. The chorus leader declares that Dionysus has received justice. Dionysus reads the riot act to Agave and her father Cadmus. Both are then exiled from Thebes. Dionysian religion is now established in Thebes, at the expense of the destruction of its royal house.

In a final myth, pirates kidnap the young Dionysus, whom they mistook for a noble youth, whom they plan to hold for ransom. When they took him on board their ship, he magically shed his shackles. Realizing that their prisoner was a god, the helmsman urged the other pirates to release him, but they refused. Dionysus caused grapevines with clusters to grow over the mast and sails, turned the ropes into ivy, and the oars into thyrsoi. Sweet-smelling wine gurgled onto the deck of the ship. Dionysus turned himself into a lion and caused a bear to appear. The terrified pirates jumped overboard and were turned into dolphins, except for the helmsman whom Dionysus saved.

In all these myths, people fail to recognize the god and his divinity, and they are punished for it in narratives that involve vines and wine as instruments of his divine power. In many other instances, Dionysus was said to have turned water into wine and vice versa, again showing his divine powers. Such myths also illustrated that divinity lies within wine, grapes, and grapevines.

The Mysteries of Dionysus

Because worshippers felt the presence of Dionysus within them when they drank wine, they felt a personal connection with him more than with other deities. Because he represented the divine force of indestructible life (zoe), he was thought to be a means for achieving eternal life. Thus, he was a savior figure. This belief led to the establishment of Dionysian mysteries, in which devotees drank wine and conducted rituals designed to ensure eternal life. In practice, over time these mysteries became mainly entertaining social gatherings for the wealthy rather than serious religious rituals. Corruptions of these mysteries led to the Bacchanalia infamous in Rome. The mysteries lasted from Hellenistic times through the Roman empire, until the triumph of Christianity.

The Legacy of Dionysus

Possibly one reason for the triumph of Christianity was that gentiles in the Greco-Roman world were already used to a resurrected divinity associated with wine with whom they could have a personal relationship as their savior and through whom they could attain eternal life. After all, Jesus turned water into wine, claimed that “I am the true vine“ (possibly in contrast to Dionysus, the false vine), and at the Last Supper said that the wine was his blood. Gentile converts to Christianity could easily discern in Christ many divine qualities that they were already used to and expected in their personal savior. Such wine associations continued into Christian Europe, where in art Christ was depicted as suffering on a grapevine cross or in a wine press whose beam was a cross; he was also depicted enthroned in heaven among grapevines, meaning that heaven was a vineyard.

Sources for Further Reading

*Disclosure: links to Amazon are affiliate links and I (Becca) might make a few cents if you purchase any item using these links. Thank you!

Isler-Kerenyi, Cornelia. Dionysos in Archaic Greece: An Understanding Through Images. Leiden: Brill, 2007. Interprets Dionysus and his involvement with wine through the art of vase paintings.

Kerenyi, Carl. Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976. Detailed and valuable interpretation of the god.

McGovern, Patrick. Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003. The leading work on the ancient history of wine, with some discussion of the related religion and myths.

Nilsson, Martin. The Dionysiac Mysteries of the Hellenistic and Roman Age. New York: Arno Press, 1975. A classic treatment of the subject including wine consumption.

Otto, Walter. Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1965. Another classic treatment of the god.

Seaford, Richard. Dionysos. London and New York: Routledge, 2006. A succinct treatment with a final chapter summarizing the dialogue of Dionysus with early Christianity.

Tilborg, Sjef van. Reading John in Ephesus. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1996. Discussion of the religious background in the likely place where the Gospel of John was written, including the influence of Dionysus.

3 comments for “The Wine Myths of Dionysus – A Guest Post by Arthur George”