Terroir: the ever elusive concept of a physical interaction between the soil and the flavors and aromas of a wine made from grapes grown in that environment. Does it exist? Scientifically, the jury is still out. So far, there hasn’t been a study to directly link soil

Photo courtesy Flickr user Ryan O’Connell

characteristics to the aromas and flavors of a given wine, however, given the complexities of the subject, studies are still ongoing. (For a long read on the mechanisms of terroir, check out this two-part article by Dr. Jamie Goode: Part 1 & Part 2).

A new paper in the journal Food Quality and Preference aimed to address the issue of terroir, specifically as it relates to identifying where a wine comes from solely by the smell. According to the researchers, if terroir (as defined by a direct link from the soil to the wine) exists, then someone should be able to sense this influence upon tasting or smelling the wine. While most studies tend to focus on multisensory inputs (taste, smell, mouthfeel, etc.), the researchers of this new study claim that no one has yet to perform a study focusing on just one aspect: odor.

The goal of this study was to ultimately determine if people could tell the difference between wines based on terroir (supposedly), and to determine if there were any differences in this ability between experts and novices.

Brief Methods

The wines used in this study were from the Berici and Euganei hills regions of Italy and from the 2012 and 2013 vintages.

All wines were sent through an olfactometer in order to maintain “odor consistency”. In other words, in case one wine had a much more pungent nose than another, the computerized olfactometer was brought in keep all wines on a level playing field so to speak. They wanted to be able to have the participants focus on the odors themselves and not be confused or swayed by varying aromatic intensities.

This study had three parts: 1) a training phase; 2) a “olfactory discrimination task”; and 3) questionnaires.

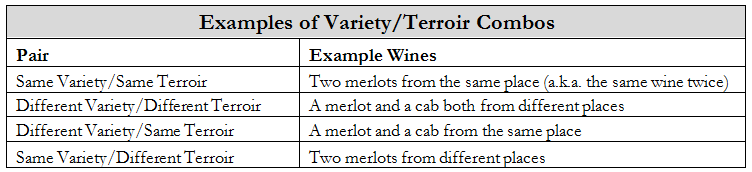

The training phase was more or less a practice run, where participants were presented with two wines and were asked to determine if they were different wines or the same wine twice. There were a total of 10 pairs for this run.

For the olfactory discrimination task, participants were again presented with two wines and were asked to determine if they were different wines or the same wine twice. There were a total of 96 pairs for this part of the study. The wines were sent through an olfactometer, where odors were presented to participants at a controlled concentration of 3L/minute. 1.5L/min of clean air was also passed through at the same time, so as to not overwhelm the senses too much during any given part of the task.

Participants were told when to inhale, with each odor presented for 2 seconds (with a 5 second break in between the two odors). At the end of the second odor, participants were asked whether the two odors were the same or different. Participants were also asked to rate how confident they were with their answers.

The 96 pairs of odors were divided as such: 30 same variety/same terroir, 44 different variety/different terroir, 8 different variety/same terroir, and 14 same variety/different terroir.

Finally, participants completed questionnaires focusing on demographics, drinking habits, and their experience with wine.

Selected Results

Participants

- 32 volunteers participated in this study (17 women, 15 men; average age 35.63 years).

- 12 (7 women, 5 men) self-reported as wine professionals, while 20 self-reported as novices (10 women, 10 men).

- At any given time, novices reported drinking about the same number of glasses as the wine professionals, though over the course of a month, they consumed much less.

The rest of the study

- Both novices and experts were able to accurately discriminate the different variety/different terroir wine pairs as well as the same variety/different terroir wine pairs, with no significant differences between responses based on experience.

- Wine experts were not able to discriminate (with statistical significance) the different variety/same terroir wine pairs. (The result for the novices were below chance, indicating a possible sampling error).

- The different variety/same terroir and same variety/different terroir pairs exhibited a significant decrease in discrimination sensitivity compared with the different variety/different terroir pairs.

- In other words, it was way easier to discriminate between the different variety/different terroir pairs compared with the other two combos listed above.

- The discrimination sensitivity of the same variety/different terroir pairs was significantly better than that of the different variety/same terroir pairs.

- Both novices and experts showed a significant bias toward the “different” response.

- In other words, more often than not, participants would say the wines were different than the same.

- Responses to the questions regarding whether or not the wines were different were faster when the participant had more confidence in his/her response.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of this study suggest that people can accurately tell the difference between wines just by smelling them, regardless of if they are experts or beginners. Have a merlot and a cab from two different places? People can tell that the wines are different, no problem (they might not be able to tell which variety is which, but that wasn’t important to the study and was thus not tested). As a side note, it was interesting to see that there was no different between novices and experts in terms of their abilities to discriminate between the different wines (again, the differences may lie in more detailed descriptions of the smells, but basic “same or different” discriminatory abilities appear to be the same).

The most interesting result was that not only could participants tell the difference between different varieties from different places, but they were also able to tell the difference between the same variety from different places. In other words, a merlot from one region smelled different than another merlot from a different region. According to the researchers, this means that participants could “smell the terroir”.

This is where I have to disagree (or if not disagree, then just question in general).

How in the world do we KNOW that terroir is the sole reason behind the participants’ ability to discriminate between two wines based on their smell? Say you have two wines: a merlot from winery X and a merlot from winery Z. You smell them. You say “hey! Those are different wines!”. From that result, how can we extrapolate that to “what I smell is terroir”?

Photo courtesy Flickr user emdot

Is it possible that the wines smell different as a direct result of the soil the grapes were grown in? Sure, maybe. BUT, isn’t it also possible that the wines smell different because they were made a different wineries with different winemakers/staff and with different viticulture and winemaking practices? Maybe the wine smells different because winery X used one particular reagent that caused a chain of reactions to yield one smell, while winery Z used a different reagent that caused a different chain of reactions to yield a completely different smell.

All we know from the method section is where the wineries were located, and whether or not they employed conventional or biodynamic style viticulture/winemaking practices. Last I checked, there were quite a variety of procedures within both styles, so the likelihood of there being differences in some practices between wineries is high.

To quote Dr. Jamie Goode (see the links in the first paragraph of this post to read the entire two-part article);

“The traditional, old world definition of terroir is quite a tricky one to tie down, but it can probably best be summed-up as the possession by a wine of a sense of place, or ‘somewhereness’. That is, a wine from a particular patch of ground expresses characteristics related to the physical environment in which the grapes are grown.”

If terroir is strictly the result of the interaction between the physical ground in which grapes are grown and the organoleptic characteristics of a given wine, then any other procedure, vini- or viticultural, that might alter the wine can’t be referred to as “terroir”. So, in essence, while the results of the study highlighted in this post have shown that people can smell the difference between two wines from different places, there is no way to know if they are, in fact, “smelling terroir” as the researchers suggest, or perhaps smelling the varying viticulture and/or winemaking procedures employed by different wineries.

There are other likely problems with this study (I’m thinking sample size, possible sampling errors, and biases, etc.), but I won’t go into those now and make this post even longer than it already is. I would encourage you all to discuss other issues (or good things!) you might have with this study in the comment section below, if you’d like.

Source:

3 comments for “Smelling Terroir: A New Study Suggests People Can Smell the Difference Between Wines Solely Based on Terroir (but can we, really?)”