I think it’s blatantly obvious that people have different taste preferences: from food and wine to coffee and cake; if you grab someone off the street and ask them their taste preferences they will say something different than if you grabbed someone else and asked them the same question.

OK, but why is it that we have such variability in our taste preferences? Is it a result of what our mothers or fathers shoved down our gullets when we were young and developing our tastes (or disdain) for certain things? Or are we genetically predisposed to enjoying certain things over others?

Turns out, it’s probably a little bit of both, however, recent studies over the past 3 or 4 years have found that genetic variation in oral sensory abilities might very well have the greatest influence on food and beverage preferences. From a

By William Lawrence (originally posted to Flickr as Geeks Love Wine) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

As an aside: Tim Hanni, MW, structured his work around similar concepts, creating the New Wine Fundamentals and Vinotypes, which “allow you to discover your true taste preferences and confidently explore a new world of wines” (quote from myVinotype.com). I highly recommend you visit his site and explore this fascinating world of discovering your unique wine preferences!

Research on the genetic variation of taste preferences has often focused on how individuals respond to the bitter compound 6-n-propylthiouracil, also known as “PROP”. This responsiveness places individuals in the different “PROP taster status” categories (a.k.a. phenotypes) of 1) PROP non-tasters; 2) PROP medium-tasters; and 3) PROP super-tasters. Those in the non-tasters group notice very little to no bitterness; the medium-tasters notice a mild bitterness; and the super-tasters notice an intense bitterness. Genetic research has found that this variation is due to variations in the TAS2R38 gene, though variations in this gene alone may not explain all variation in taste sensation and preferences.

Those that are PROP super-tasters are often characterized as having greater sensitivity to sour, salt, sweety, and creamy, and also display greater sensitivity to astringency, bitterness, and sourness in alcoholic beverages. Some say that being a PROP super-taster also predisposes them to being more “acute tasters”, allowing them to pick up more subtle or less obvious tonal nuances in the food or beverage they are tasting. Depending upon which PROP category / phenotype of which one expresses, the “liking” or preference of particular foods or beverages will change. Interestingly, PROP categories / phenotypes have been linked in some research studies to diet-related diseases, including obesity and alcoholism.

Though it hasn’t been supported nor disproved in the research literature, it is believed that “foodies” (i.e. those that have “a high liking of food, significant time spent preparing food and choosing ingredients, and a high knowledge of

By Alpha from Melbourne, Australia [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

In regards to wine expertise, research has shown that PROP phenotype varies depending upon one’s level of wine expertise, with wine experts experiencing greater PROP sensitivity (i.e. super-tasters) and wine novices experiences less PROP sensitivity (non-tasters or medium-tasters). In theory, one may expect that foodies and wine experts do not differ in their PROP sensitivity,

One very recent study aimed to address these questions regarding foodies and wine experts and their propensity towards exhibiting a particular PROP phenotype and examined whether or not foodies and wine experts differ from other people in regards to their PROP sensitivity, and whether the PROP sensitivity of the two are similar or unrelated.

Methods

A mail survey/questionnaire was utilized in this study. 5000 surveys were mailed out, 1,011 were returned, and 954 were complete enough for use in statistical analysis (100% complete). To encourage completion of surveys, cash prizes were awarded (between $20 and $500 USD).

Surveys were mailed to random wine consumers that were on the mailing list of a large wine retailing group in the Northeast of the United States.

The surveys asked participants to rate their “liking” of 64 food items and 14 non-food items. The food items selected represented a wide range of nutritional groups and values. Non-food items were randomly placed throughout the food items on the surveys.

Participants were asked to rate their level of wine expertise as novice or beginner, intermediate, high, or expert/very high. Demographic information was also collected.

PROP phenotypes were determined using filter paper disks that were previously treated with 50mmol/L of PROP. These disks were included with the surveys that were mailed to participants. After the surveys were completed, participants were asked to use the PROP disk and rate their experience.

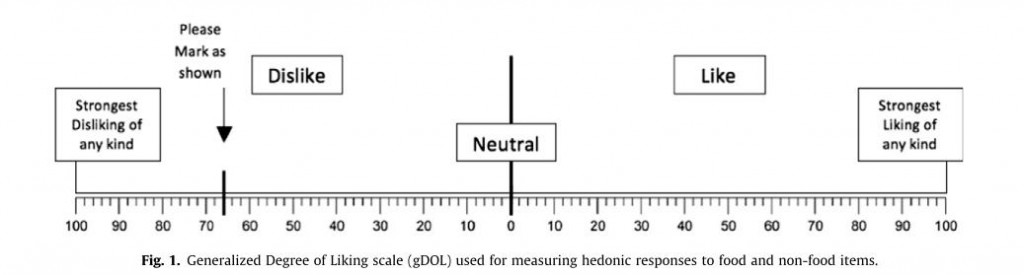

The instructions for using the PROP disks were to “take a sip of water and swish it around your mouth to clean it. Take the paper disc and place it on the tip of your tongue for 30 seconds or until it is fully wet. Rate the intensity of the taste of the paper disc by drawing a mark on the scale for your answer”. (Pickering et al, 2013). Participants were shown a scale with marked degrees of “likeness” and were asked to pick where on the scale their liking of the disk fell. See Figure 1 for this scale. Participants were also supplied a picture representation of the instructions for greater ease of use.

Participants were classified as non-tasters if their liking fell in the less than 9mm portion of the scale; medium-tasters if their liking fell between the 9 and 50mm portion of the scale; and super-tasters if their liking fell in the greater than 50mm portion of the scale. Again, see Figure 1.

Results

- Gender analysis found that women rated PROP bitterness as more intense than men, indicating women were more likely to be super-tasters than men.

- Women ranked PROP bitterness 35% higher than men.

- Age analysis found that there was a small decline in PROP bitterness intensity with age.

- This may be due to the decline in olfactory function as one ages.

- In regards to foodies, the authors assumed that foodies would give higher score to food items than non-food items compared to non-foodies; however, results found that there was no such association found between foodies and PROP bitterness intensity.

- Foodies tended to be older than non-foodies:

- 51% of foodies were over the age of 61.

- 29% of non-foodies were over the age of 61.

- Foodies were also found have more individuals retired, and more with larger incomes, both the researchers attributed to the age factor mentioned just previously.

- Non-foodies were more likely to be female.

- In regards to wine expertise, there were many significant findings.

- Wine experts rated PROP bitterness higher than wine novices.

- Women ranked PROP bitterness higher than men.

- PROP bitterness intensity decreased with age.

Conclusions

Several important results can be pulled out of this study. First, it appears as though there is no evidence to support the theory that foodies have increased PROP bitterness intensity or exhibit super-tasting capabilities. The authors mention several limitations to this study in regards to this result suggest that perhaps the criteria for labeling someone as a foodie in this study was too general, resulting in non-foodies being mistakenly identified as foodies in this analysis.

In the future, the authors suggest further increasing the criteria to be categorized as a foodie to include “time spent preparing food and choosing ingredients; knowledge of food, preparation methods and ingredients; and enjoyment at learning about new foods and food preparation methods.” (Pickering et al 2013). Also, adding in more “refined” or “complex” foods to the food item list of the survey may help distinguish foodies from non-foodies.

The authors noted that there could have been difficulties distinguishing differences between foodies and non-foodies in regards to the PROP sensitivities, since the sample used to collect data from was bias. If you recall, the sample was collected from a mailing list at a wine retailer, so customers were already more interested in wine than the average person, which could have biased the entire sample toward having somewhat more intense PROP scores in general than someone who rarely drinks wine. The people on the wine retailer’s mailing list may have been already more likely to be foodies due to their status as wine lovers than someone else who didn’t voluntarily sign up for the mailing list. The study should be repeated capturing a greater number and variety of individuals to determine if these results are repeatable, or if they are only applicable to this smaller group of relative bias.

Another result the authors made sure to note was the fact that wine experts tended to be super-tasters compared to less experienced wine drinkers that were either medium-tasters or non-tasters. They hypothesized that because of this propensity and genetic predisposition to be super-tasters, individuals may be drawn to careers in the wine or food industry. It would be interesting to see a long-term study where they measured the PROP bitterness intensity scores of

By Agne27 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

I would also like to see future research investigating the gender result further. You may recall, this study found that women scored higher PROP intensity scores than men. What does this mean? Are women better tasters than men? There has been some research to suggest this may be the case, but of course, this has been met with some controversy. They authors didn’t mention much about this in the conclusions, though since it wasn’t their primary focus, I’m not surprised. I would love to see this result studied further. In the meantime, please read a guest post by Marlene Rossman on The Academic Wino regarding this very topic: Women Smell Better!.

Finally, the authors brought up a very fascinating question regarding the use of wine experts’ recommendations to encourage the purchase of particular wines. It has been shown that people do find expert opinions important when choosing a wine, as it takes some of the “guess work” out of figuring out if the bottle is “good” or not. The problem with that, the authors raise, is that the differences in PROP bitterness intensity scores of experts versus novices is that experts are inherently going to like and enjoy a certain type of wine, while novices are more likely to enjoy a different type of wine. This isn’t always going to be the case, but since PROP intensity scores dictate taste preferences, it is fair to assume that the wine the experts deem “quality” and “good tasting” will end up being less enjoyable to the wine novice who prefers a different tasting wine. This calls into question the usefulness on solely relying on expert opinions to sell wine, and to encourage the use of other marketing strategies to capture those on all ends of the wine preference spectrum.

I’d love to hear what you all think about this topic! Please feel free to leave your comments and join in the discussion!

Source: Pickering, G.J., Jain, A.K., Bezawada, R. 2013. Super-tasting gastronomes? Taste phenotype characterization of foodies and wine experts. Food Quality and Preference 28: 85-91.

6 comments for “Wine Experts and Foodies: Are They Super Tasters? Or Are They Faking It?”