Many studies related to consumer choice in wine rely on self-reported level of understanding

Photo By OneArmedMan – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2979217

and knowledge of wine. I’ve included many of those kinds of studies here on this blog—here are just a few examples of studies that utilized self-reported expertise levels reviewed here on The Academic Wino, “Wine Experts and Foodies: Are They Super Tasters? Or Are They Faking it?”, “Putting Wine Awards On The Bottle: A Study of Consumer Purchase Behavior”, “How Much is Too Much? A Study on Choice Overload in Wine Retail”, and “The Influence of Wine’s Reported Health Benefits on Consumer Purchase Behavior”.

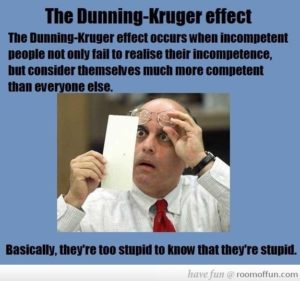

Despite many studies using this method of wine expertise evaluation, is it accurate and/or appropriate? These studies will often use self-reported wine knowledge levels to separate research participants into different groups during a test or experiment, with the ultimate goal often being to evaluate consumer purchase behavior for a specific demographic for marketing and sales purposes. According to a short communication study in the April 2018 issue of the journal Food Quality and Preference, using self-reported accounts of expertise can sometimes run afoul with what is known in the field of psychology as the Dunning-Kruger effect.

Simply put, the Dunning-Kruger effect, a phenomenon named for a 1999 study by David Dunning and Justin Kruger, is when someone with very little knowledge of a subject overestimates what they know, making themselves appear more knowledgeable than they really are, and also when someone expert knowledge on a subject doesn’t think they know as much as they do or assumes that a task that seems easy to them is easy for everyone else. Quoting directly from the 1999 paper (which is cited in the Food Quality and Preference article I’m highlighting today): “unskilled individuals suffer a dual burden: not only do they

Photo courtesy Flickr user Silly Deity

perform poorly, but they fail to realize it. It thus appears that extremely competent individuals suffer a burden as well. Although they perform competently, they fail to realize that their proficiency is not necessarily shared by their peers.”

The Dunning-Kruger effect has been studied and shown in many different industries and for many different skill sets, so could it be possible this effect is also present for wine-related knowledge? Could the self-reported wine experts be downplaying their knowledge? Or perhaps some wine novices are mistakenly placed in higher expertise level categories based on their overestimation of their wine knowledge? Today’s study aimed to examine just that.

Brief Methods

193 people (126 men, 67 women) between the ages of 26 and 55 participated in this study. All were enrolled as students in academic programs for executives at a university in Chile.

Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire containing both subjective and objective question related to wine (the order of which were randomized). The questionnaire was divided into four parts: 1) rating wines based on brand, region, price, and look of the bottle; 2) a set of questions with either subjective and objective questions aimed toward determining their level of wine knowledge; 3) their wine consumption habits, and 4) a set of questions with the other type of questions not asked in the second section (i.e. some people had the subjective questions in part 2 and objective questions in part 4, while others got them in reverse order). Questions on demographics were also asked.

Wine-related questions were developed with help from three actual wine experts (not just self-reported).

Results

- Based on their scores of the objective questions, participants were placed into one of four categories: 1) lowest objective knowledge, 2) low objective knowledge, 3) high objective knowledge, and 4) highest objective knowledge.

- For all groups, there were significant differences between the objective and subjective scores.

- There was significant overestimation of wine knowledge found in those in the lowest objective knowledge group.

- There was significant underestimate of wine knowledge found in those in the highest objective knowledge group.

- While the least knowledgeable group overestimated their wine knowledge and the most knowledgeable group underestimated their wine knowledge, only 25% of the variance in subjective knowledge could be explained by the variance in objective knowledge, meaning that there are multiple reasons why someone may be over or underestimating their wine knowledge.

Conclusions

Not many results to report here, as they study itself was short and sweet, but those results that were presented seemed to provide evidence for the presence of the Dunning-Kruger effect in wine. Specifically, the study found that those who had the lowest scores on the objective portion of the test (i.e. the true “wine novices”) grossly overestimated how much they actually knew about wine, and those who had the highest scores on the objective portion of the test (i.e. the true “wine experts”) grossly underestimated what they know about wine.

So, does this mean that the results of all studies using self-reported wine expertise/knowledge is incorrect? Not necessarily, as not everyone misinterprets their level of knowledge, however, it does suggest that results from studies solely utilizing self-reporting

Photo courtesy Flickr user Bill Eyer

of wine knowledge levels should be taken with a grain of salt. Researchers might be better off to combine self-reported information with other objective-based methods for determining expertise/knowledge levels, or just not use self-reporting all together if it’s possible.

A few limitations to note: this study only utilized one method for obtaining subjective and objective knowledge on the subject of wine, when in fact there are many more tools available to ascertain similar ends. More tests utilizing other data collection methods would provide more support (or not!). Additionally, this study took place in only one area of the world—Chile—would we see the same results if the test were performed in France, the US, or anywhere else in the world for that matter?

Overall, the results of this test seemed to provide evidence for the Dunning-Kruger effect as it relates to wine knowledge, and that one should be aware of the possible cognitive bias when evaluating market research on wine when subjective self-reported wine expertise is the only method of data collection provided.

Source:

1 comment for “False Expertise and Humble Connoisseurs: The Dunning-Kruger Effect in Wine”